The Genesis and Strategy for Operation Overlord

The Genesis of the Normandy Landings

Following the entry of the United States into the war in December 1941, the Allies decided to coordinate their military action against the Reich. While the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was in favour of a landing in the Mediterranean, the Americans preferred a cross-Channel landing followed by a major breakout early in 1942. The disaster of the Anglo-Canadian Dieppe raid quickly put an end to this project. The date was too early and Operation Torch, the landings in North Africa, took priority. The plan to open a second front in the west, which Joseph Stalin had been advocating with the Allies for some time, was studied once again in May 1943. Codenamed Overlord, the operation was planned for May 1944. The zone on the French mainland between the River Orne and Cherbourg was chosen for establishing a bridgehead on the coast of Western Europe.

The Choice of Normandy

From May 1943, the Allied High Command had to take a decision about where to land, somewhere between the North Cap and the Spanish frontier. The necessary conditions were clearly defined, the presence of a large port near the landing coast, low lying beaches, a hinterland ideal for a break out by armoured forces and a coastline within close proximity to British airfields.

Two sectors were selected for consideration Normandy and the Pas-de-Calais, the latter was closer to England but more heavily defended than Normandy. The fortifications of the Atlantic Wall, which had been built by the Germans, in the more distant Normandy region were less substantial and were, above all else, not completed. The Norman beaches were protected from violent storms and were in close proximity to the port of Cherbourg. The region could also be easily isolated from the rest of the country by destroying the bridges over the Rivers Seine and Loire. Reconnaissance of these sectors had already been carried out by British commando forces in 1941 and 1942. After the raid on Dieppe, on which many had pinned their hopes but, turned out to be a total failure, the raids along the Channel Coast began again.

The first modifications to the Overlord Plan

The initial plan was to land over 40 kilometres of coastline from Courseulles to Grandcamp. The landing front was considered too narrow by the Supreme Command and was extended to the west to include the eastern seaboard of the Cotentin Peninsula and to the east up to the estuary of the River Orne. From Quinéville to Ouistreham, the new landing front which was adopted in February 1944 extended over 80 kilometres, doubling the front of the initial plan. The increase in the length of the coast obliged the Allies to reconsider the number of divisions which were to be engaged, their transport and, in consequence, the date of a landing. The date was determined by three factors: the landing should take place before dawn, at a rising low tide and with a full moon to facilitate the deployment of the airborne forces. These conditions were only available several days a month. On 17th May, the Supreme Allied Commander fixed the date of a landing for 5th June, or 6th or 7th if the weather was unfavourable.

Operation Fortitude

Before the landings on the French Coast, the Allies carried out a vast operation of deception, codenamed Fortitude, to convince the German forces that a landing would take place in the Pas-de-Calais. The Allied Intelligence Services inundated the German forces with false information about where and when a landing would take place. Huge fictitious armies were installed in Kent, in the south east of England. Imitation airfields, fuel storage centres, inflatable vehicles and wooden aircraft were aligned in the fields and along the roadways… Bombing and reconnaissance missions were carried out frequently in North and North Eastern France. A fictitious High Command under General Patton was created, FUSAG, First United States Army Group. Bogus headquarters, infrastructures, store depots were created and false coded radio messages were sent from Montgomery’s headquarters. In May 1944, Field Marshal von Rundstedt was convinced that a landing would take place north of the Seine. The Allied ploy was so successful that the German forces were certain that there would be a considerably larger landing, than that of 6th June, in the Calais region in July.

Actors and Forces present

Allied Forces

On the eve of 6th June, three million soldiers, 1.7 million of them American, were assembled in England: 39 divisions, 20 American, 14 British, 3 Canadian, 1 Polish and 1 French Division. The air force had 11,600 aircraft at its disposal: 3,500 fighters and 5,000 bombers and 7,000 ships, of all types were ready to set sail for France. Operation Neptune, the naval assault, had prepared five naval forces, which had assembled off the Isle of Wight, at a designated position codenamed “Piccadilly Circus”, to approach the five landing beaches. At dawn on 6th June, six divisions would land 1st, 4th and 29th American Infantry Divisions, 50th and 3rd British Divisions and 3rd Canadian Division. Three airborne divisions would land on the night of 5th/6th June, 6th British Airborne and 82nd and 101st American Airborne Divisions. A total of 17,000 men would be rapidly supplemented by 13 additional divisions on D-Day plus one and 17 more divisions on D-Day plus three.

The German High Command in the West

Hitler had long awaited a landing in the west. Rumours from the Tehran Conference confirmed his suspicions in the spring of 1944 that there would be a cross-Channel landing. Field Marshal von Rundstedt, the commander of the German forces in the west and a soldier of the old school, had little confidence in the Atlantic Wall and like Hitler was skeptical of a landing in Normandy. His command consisted of two armies Army Group G, to the south of the River Loire, commanded by General von Blaskowitz and Army Group B, to the north, commanded by Field Marshal Rommel since 15th January 1944.

While von Runstedt counted on flexible forces, kept in reserve, capable of repulsing an aggressor, Rommel was convinced that the Allies should be thrown back into the sea in the first hours of a landing; therefore, the role of the Atlantic Wall was vital for Rommel. He considered a landing on the Norman beaches the greatest threat. The German armoured forces were commanded by General von Schweppenberg but, could only be engaged in combat, along with Krancke’s naval force and Sperrle’s air force, on Hitler’s orders. During the first days of the battle, the Germans paid heavily for this dysfunction and the overly centralised command under one man, Adolf Hitler.

German Forces in Normandy on 6th June

Since his arrival on the western front, Field Marshal Rommel, who was responsible for the Atlantic Wall, had constantly requested reinforcements. In May 1994, Hitler, now convinced that a landing would take place in Normandy, sent fresh troops to the Cotentin (91st Division and 6th Parachute Regiment) and to the Eure region (12th SS) Simultaneously, forces based in the sector (352nd) were moved forward to the landing coast. With six infantry divisions and two armoured divisions (21st and 12th SS), the enemy was a redoubtable force. However, Hitler’s divided command structure, which deprived the commander in the west (Rommel) of reserve forces, created friction amongst the generals and weakened their capabilities. The Luftwaffe, which no longer had air supremacy, had only 500 aircraft at its disposal in Normandy.

The Atlantic Wall

Field Marshal von Rundstedt, the commander of German land forces in Western Europe, was responsible for the defense of 5,000 kms of coast. From June 1940, the Germans were content on defending the coastline between Calais and Boulogne in preparation for an invasion of Britain. However, from December 1941, an entirely defensive strategy was adopted, as the danger for the Germans could come from the west. The construction of the Atlantic Wall began early in 1942 around the principal ports in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais with the installation of U-Boat bases, batteries, bunkers and radar stations. The objective of 15,000 concrete fortifications constructed on the eve of D-Day was far from this figure. By late 1943, only 8000 fortifications had been built. In January 1944, Rommel, who was responsible for the Atlantic Wall along the coast of France, rapidly highlighted the faults in the defensive system. Within several months, Rommel’s forces had built more than 4,000 fortifications and installed 500,000 obstacles on the beaches and in the hinterland. In Normandy, by June 1944, 2,000 fortifications, 200,000 obstacles and two million mines were in place. Despite this attempt to make up for the deficit, much of the construction was uncompleted at the time of the landings.

The differences of opinion between Rommel and von Rundstedt was a major cause in the delayed construction of the French coastal fortifications.

Eve of Battle (1st-5th June 1944)

Messages sent by the BBC

At 1330 hours on 1st June 1944, over the radio waves of the French Service of the BBC, a message was broadcast destined for the Resistance in France “L’heure du combat viendra”. This message was destined, in particular, for the members of the Resistance in the “M” Region, the 14 departments (counties) in Western France. Amongst the 160 other messages broadcast that day, were the first three verses of the poem by Verlaine “Les sanglots longs des violons de l’automne”. Repeated on 2nd June, this message preceded the 210 messages which would be broadcast during 16 minutes on 5th June. Amongst them, messages indicating to take up arms: “Les dés sont sur le tapis” (installation of the “Plan Vert”, the sabotage of the railway network) “Il fait chaud à Suez” (activation of the partisan network) followed by “Bercent mon coeur d’une langueur monotone”. This last verse of Verlaine’s poem was not destined for the entire resistance network as the Germans believed, having infiltrated several resistance units of the SOE, but was for a particular resistance unit, codenamed “Ventriloque”, operating in the Loir-et-Cher. The resistance in Normandy set to work, it blew the Paris to Cherbourg railway line north of Carentan and the Saint-Lô to Coutances line, the railway lines between Paris and Granville at Saint-Manvieux, and the Caen to Bayeux and Caen to Vire were also cut. Telephone communications, connecting the headquarters of 84th German Corps at Saint-Lô to 91st Infantry Division based at Valognes, were also destroyed along with the telephone lines between Saint-Lô and Jersey and Brest and Cherbourg.

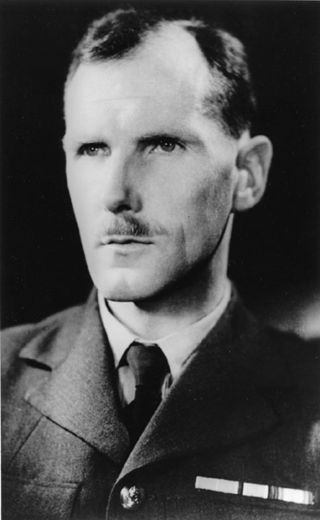

Group Captain Stagg’s Weather Reports

On 2nd June at 2130 hours the first unfavourable weather forecasts were presented to Eisenhower by Group Captain Stagg, the chief meteorologist at SHAEF Headquarters. Despite the forecast, the plan and the date for the landing remained unchanged. On 3rd June, at 2130 hours, due to the very bad weather conditions, Eisenhower decided to provisionally postpone the landings. But, by 0415 hours on 4th June following a conference at SHAEF headquarters, Eisenhower had ordered a definite postponement of 24 hours. The order was immediately given to recall the convoys which had already sailed. On the evening of 4th June at 2130 hours, during another conference and while the south coast of England was battered by a storm, Eisenhower delayed taking a final decision until the morning of 5th June. At 0415 hours, Group Captain Stagg’s weather forecast gave some hope. A calm period of weather, lasting 36 hours from the morning of 6th June, finally led to a decision being made to go ahead with a landing the following day at dawn.

General de Gaulle is sidelined

On 3rd June 1944, the French National Liberation Committee, in Alger, declared itself the Provisional Government of the French Republic and General de Gaulle accepted an invitation from Winston Churchill to come to Great Britain. De Gaulle flew that evening from Alger, via Morocco, to England. General de Gaulle arrived at Northolt airfield on 4th June at 0600 hours and made his way to join Churchill for lunch at 1330 hours in his armoured train near Portsmouth. It was at this meeting that he was given an overview of Operation Overlord. In the afternoon, de Gaulle and Churchill joined General Eisenhower at his headquarters at Southwick House.

General de Gaulle was invited by his hosts to record a BBC broadcast, which had been prepared and drawn up by Eisenhower himself. This broadcast, in which French legitimacy was not even mentioned, provoked outrage from de Gaulle and an angry argument with Churchill. De Gaulle refused to make the broadcast; he left SHAEF headquarters and returned to London. The evening of 6th June, de Gaulle broadcast his own famous speech “La Bataille Supreme est engageé…”

German Inertia

On 5th June at 0700 hours, Field Marshal Rommel, commander of Army Group B, left his headquarters at La Roche-Guyon by car. Rommel was heading to Germany to visit his wife at their home at Heerlingen and also to meet with Hitler to request armoured reinforcements for Normandy.

Due to the unfavourable weather conditions at this time, Admiral Krancke, the western naval force commander, while on a tour of inspection at Bordeaux, ordered all naval forces in the Channel to stand down.

Meanwhile, the commander of 21st Panzer Division, the only panzer division deployed in the Caen area, was in Paris with a mistress.

The first indications of a potential landing were arriving at the various headquarters. Towards 2130 hours, Lieutenant Colonel Meyer, head of counter intelligence of 15th Army, informed his superior, General von Salmuth, of the broadcast of the second part of the Verlaine poem indicating that a landing was imminent. General von Salmuth immediately put 15th Army on alert and informed von Rundstedt’s headquarters. Despite the alert, the German forces were far from ready for battle. General Dollmann, commander of 7th Army in Normandy, was absent at Rennes preparing an exercise, with his divisional and regimental commanders from Normandy and Brittany, for the following day. Only the commander of 91st Infantry Division, General Falley, suspected, due to the increase in air activity, that the situation could be critical and returned to his headquarters at Picauville in the Manche district. At midnight, General Marcks, commander of 84th Corps responsible for the sector between the Rivers Dives and Couesnon was celebrating his birthday at his headquarters at Saint-Lô. The 7th German Army, to which Marcks’ force was attached, had not been averted about the messages sent by the BBC. General Marcks was unaware that, at that very moment, the Allies had launched their airborne operations while simultaneously, in Brittany, French parachutists jumped into the Maquis de Saint-Marcel.

In Brittany, on the night of 5th-6th June, Major Bourgoin, commanding four sticks of parachutists from 2nd Regiment of “Chasseurs Parachutists” jumped into the Saint-Marcel region of Brittany. Once on the ground, their role was to set up two supply bases from where groups, carrying out sabotage, could set out to try and prevent 150,000 Germans stationed in Brittany heading to Normandy. Their mission was also to coordinate the 20,000 members of the “Maquis” who had formed for the upcoming battle.

At 0045 hours, two sticks, commanded by Lieutenants Marienne and Déplante, were dropped into the Morbihan district between Plumelec and Guehenno, the mission was codenamed “Digson”.

In the Cotes-du-Nord, two other sticks commanded by Lieutenants Botella and Deschamps, in a mission codenamed “Samwest”, were also dropped towards 0115 hours on the edge of the Duault forest.

These four sticks were the vanguard of a vast airborne operation planned for the following day when 18 teams were to be deployed. The first wave of 36 parachutists served in 4th Special Air Service commanded by Major Bourgoin. The two base camps were the hubs for specific missions to be carried out following the Allied landing in Normandy: to cut lines of communications, confuse the enemy and to make contact with the local resistance units. The operation was carried out reasonably successfully in the Cotes-du-Nord but was not so successful in the Morbihan. The paras landed less than 800 metres from a German observation post. Alerted, the enemy, composed of Georgian troops, rapidly encircled the parachutists before attacking. Out of ammunition and reduced in number, the parachutists surrendered after having destroyed their radio equipment. Amongst the prisoners, Emile Bouetard, who had been wounded in the shoulder, was killed in cold blood by the Georgians. At 0130 hours, Bouetard became the first French parachutist killed during the liberation.

The Final Phase of Fortitude

On the night of 5th-6th June, the Allies launched an operation on the Pas-de-Calais Coast. “Glimmer” was destined to convince the German High Command of the imminence of an Allied landing in this sector. “Windows” small strips of aluminum were dropped from RAF bomber aircraft off Calais and the Cap d’Antifer during three and a half hours. The objective was to confuse the German radar giving the effect of an approaching Allied invasion fleet. Fictitious radio communications and naval forces massed off Boulogne-sur-Mer and Fécamp, behind smoke screens, gave the impression of an Allied fleet. The German coastal batteries opened fire on these non-existent armadas.

Simultaneously, Operation Titanic began when 40 British aircraft dropped several hundred dummy parachutists in various sectors as part of the deception plan. Over 200 dummy “Ruperts” were dropped in the Saint-Lô area, 50 to the east of the Dives, 50 to the south west of Caen and 200 near Yvetot, along with parachutists of the SAS (Special Air Service) who had the mission of activating mechanisms, within the dummies, to diffuse the sound of guns and battle.